Wednesday, January 28, 2009

In an age when our politics have done more to divide us than to bring us together, how is it that a political event captured the feeling of a once-in-a-generation movement?

As many have noted, President Obama is a gifted orator. His rhetoric and personal appeal certainly accounts for some of that feeling. But it seems to me that an even greater portion of his power derives from the philosophy behind his rhetoric. He’s not flattering us and telling us how great we are. Neither is he calling for a fundamental shift in who we are as a nation. Rather, he’s reminding us of who we can be when we’re at our best:

"In reaffirming the greatness of our nation, we understand that greatness is never a given…it has been the risk-takers, the doers, the makers of things -- some celebrated, but more often men and women obscure in their labor -- who have carried us up the long, rugged path toward prosperity and freedom.

…This is the journey we continue today. We remain the most prosperous, powerful nation on Earth. Our workers are no less productive than when this crisis began. Our minds are no less inventive, our goods and services no less needed than they were last week or last month or last year. Our capacity remains undiminished. But our time of standing pat, of protecting narrow interests and putting off unpleasant decisions -- that time has surely passed. Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America."

His words are inspiring precisely because they speak to what we as Americans consider our best qualities – the side of us that works hard, develops creative new ideas, helps our neighbors, puts our community first, has patience with our children, and acts as a good citizen of the planet – much as Lincoln called on “the better angels of our nature." In the midst of seemingly unending wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, having lost our stature in the international community, and with our economy going into a tailspin, his appeal is above all a reminder that those selves still exist.

Whether knowingly or otherwise, Obama is drawing on a method that smart business leaders are increasingly relying upon: Appreciative Inquiry. Formalized at Case Western University, Appreciative Inquiry is a method for evolving corporate culture and improving organizational effectiveness. It seeks to build on an organization’s core strengths and capabilities to achieve better business results. In effect, Appreciate Inquiry balks the current trend toward external benchmarking, and instead builds on what’s already working well.

Appreciate Inquiry starts with a series of interviews to identify the moments when a company has been at its best, and piece apart the conditions that created those optimal results. Questions look a lot like storytelling:

- Tell us about some times when you have done great work which has significantly impacted performance within the corporation. What were the significant things you did to act as a catalyst for success?

- Tell me something you have done this year which you consider to be progressive or innovative. What key challenges did you face? What influence did you have?

(Source: Clark Amadon)

Once those conditions for success have been identified, an AI team can then look for ways to re-create those conditions more often, for more people. While Appreciative Inquiry starts with what already works well, it doesn’t discourage further evolution – rather, it identifies the most productive ways to achieve a company’s strategic goals based on its “corporate DNA.” Because AI draws on behaviors, beliefs, values, and strengths that already exist inside an organization, it tends to produce more lasting results than other types of cultural change initiatives. AI tends to enroll a greater number of people in its goals, because they can see how their existing knowledge, talents, and skills can contribute to the effort. (Incidentally, this is directly related to my post about IBM’s efforts to build on its strengths to grow the business).

That’s exactly what Obama has done: he has identified the strengths that lie in our cultural DNA, dusted them off, and reminded us that they still exist. In his call for change, he has asked us to choose the best side of each of us, both as individuals and as Americans.

We’ve already seen initial signs of success of this approach. Obama’s campaign saw unprecedented numbers of small donations from first-time givers. And his call for a day of service on Martin Luther King Jr. Day drew record numbers of participants. We don’t want to change, exactly – we don’t want to think like the Swiss, live like Koreans, or act like the British. But we do want to see progress in the workplace, in our communities, on the international stage, and in our everyday lives.

That’s not an easy task – it’s one that will require all of us to pitch in one way or another, whether through volunteerism, community outreach, changing business practices, or in myriad other ways. Even though it’s more work for everyone, for the first time in a long time, people seem excited about that call to duty. I think that’s because we want to measure up. We want to be our best selves. And in the end, that’s the most inspiring call of all.

Wednesday, January 14, 2009

Jobs Puts Apple to the Test

Best wishes to Jobs, and best of luck to Apple.

Tuesday, January 13, 2009

Building a Better Pyramid Scheme

I suspect the last time anyone was so interested in the topic was sometime in junior high.

As much as he deserves privacy when it comes to his health, it’s not altogether surprising that everyone from Mac lovers to stockbrokers has an eye on his medical status. After all, Apple’s share price seems to be directly tied to Jobs’ disposition.

Numerous industry pundits have warned of the day, looming somewhere on Apple’s horizon, when Steve Jobs is no longer directly involved with the business. Having already played the role of the white knight for the once-ailing company, Jobs’ role remains so critical to Apple’s continued health that many analysts rely on an assessment of Jobs’ operations as well as the company’s operations when making stock picks.

As much as Jobs’ personal brilliance contributes to Apple’s businesses, it also detracts from his organization’s ability to stand on its own. Jobs excels at identifying opportunities. But his company doesn’t. Instead, he has created a machine that’s primed for response – taking Jobs’ ideas and turning them into reality. That’s OK for a one-man show. But it’s unsustainable for a Fortune 500 firm.

On the other end of the spectrum is P&G. Long known for its systematic, analytical approach to marketing and new product development, P&G draws on ideas and talent from throughout its ranks to identify and pursue growth opportunities. CEO A.G. Lafley is certainly instrumental in setting vision and strategy. But Lafley’s organization is tuned for growth, not for looking to Lafley to dictate its every move.

The same dynamic is now at play in the political domain. After President Bush’s 2004 reelection, former Senator Bill Bradley noted that the underlying structure of the Democratic and Republican parties may have contributed to the victory. Bradley likens the Republican Party to a pyramid:

Big individual donors and large foundations…form the base of the pyramid. They finance conservative research centers…that make up the second level of the pyramid.

The ideas these organizations develop are then pushed up to the third level of the pyramid - the political level. There, strategists…take these new ideas and…convert them into language that will appeal to the broadest electorate. And then there's the fourth level of the pyramid: the partisan news media…

At the very top of the pyramid you'll find the president. Because the pyramid is stable, all you have to do is put a different top on it and it works fine.

The Democratic Party, on the other hand, functions as an “inverted pyramid”:

Imagine a pyramid balancing precariously on its point, which is the presidential candidate.

Democrats who run for president have to build their own pyramids all by themselves. There is no coherent, larger structure that they can rely on. Unlike Republicans, they don't simply have to assemble a campaign apparatus - they have to formulate ideas and a vision, too. Many Democratic fundraisers join a campaign only after assessing how well it has done in assembling its pyramid of political, media and idea people.

In other words, the Republican Party operates like P&G. The Democratic Party operates like Apple.

The implications of these two organizational structures are significant. Bradley credits the pyramid vs. inverted pyramid with the difference between victory and defeat in 2004. Just as importantly, these organizational structures may strongly influence the success or failure of the President’s political agenda.

That may be particularly true for President-Elect Obama. His charisma and personal appeal have inspired millions. But these same characteristics may have cornered him into being as crucial to the national policy agenda as Jobs is to every detail of Apple product development. Once Obama is out of office, distracted by foreign policy issues, or otherwise absent, these same supporters may find themselves rudderless – just as Apple was in the nineties after Jobs’ exit.

Obama’s task, then, is twofold. First, he must create the base of his pyramid – the donors, research centers, policy, and wonks that will define his administration. Second, and perhaps more importantly, Obama must flip the Democratic pyramid so that these functions lie on bottom, stabilizing, securing, and systematizing his vision. Just as Hillary Clinton had to remind her disappointed supporters that her bid for the presidency was about her ideas, not just about her personally, Obama will need to find a way to translate the enthusiasm for him into enthusiasm for something that transcends any single person.

This'll take time. After all, Giza wasn't built in a day...

Friday, January 2, 2009

Change We Can Keep

With the New Year come New Year’s resolutions. (Mine: blog more!)

And with New Year’s resolutions comes pessimism. (Uh oh.)

Amid newfound commitments to diet, exercise, visit museums, throw fabulous dinner parties, and write more in our blogs, naysayers recount doom-and-gloom statistics of the tiny number of people who will keep those resolutions past Valentine’s Day – let alone till the next time we crack open champagne and sing Auld Lang Syne.

If we can’t even stay away from the Krispy Kremes and leftover apple strudels in our private lives, how can we ever hope for groundbreaking reform in public life? Is President-Elect Obama’s “Change We Need” really change we can keep?

It seems to me that in order to make permanent the kinds of changes that are so desperately needed – improvements to our health care system, to our economic woes, to the public education system, and to our foreign policy, just to name a few – we may need to take a page from what works (and what doesn’t) in making changes to the smaller stuff. As any seasoned resolution-maker can tell you, the hardest changes to keep are the resolutions to do things you hate: exercising instead of watching TV, eating sorbet instead of ice cream, cooking healthy food instead of takeout. The easiest, of course, are resolutions to do more of the things we love: use all our vacation days, call old friends, get a new hairdo.

As simple as it sounds to keep the “easy” resolutions, I think there’s something profound in what makes those resolutions easy to begin with. The things we love are often the things we’re good at. The things we hate, on the other hand, are things that seemingly require wholesale changes to who we are or how we live our lives. We succeed at keeping resolutions when we play to our strengths – not when we try to become something that we’re not. It’s an easy lesson to remember when it comes to athletics (I’m klutzy, so I run, but I don’t play basketball), but somehow much harder when it comes to New Year’s resolutions (I will develop musical talent!).

That’s as true for corporations as it is for individuals. Companies that try to spur faster growth by copying P&G’s approach, or by being more like Nike, tend to be far less successful than companies whose growth strategies build on what they’re already good at. That doesn’t mean ignoring lessons learned elsewhere, but it does mean applying those lessons judiciously and with an eye toward an organization’s own strengths. When IBM decided to get into the services business, it didn’t succeed by becoming more like Accenture. It succeeded by becoming more like IBM. Capitalizing on its existing organizational strengths and assets to get into the services business helped ensure IBM’s long-term success.

The simple idea of playing to your strengths is hard enough on a corporate level, but it seems to disappear entirely when it comes to formulating national policy. So maybe it’s time to return to the obvious. Our national resolutions could be far more successful if we could only figure out a way to frame them in terms of doing more of the stuff we love – the stuff we’re good at as a nation.

Now for the hard part. What do you think we’re good at? And how can we apply that strength in ways that could shape national policy?

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

What Obama Learned from the Story of the Cell Phone

Any one of those would be a radical shift for America. But all of those changes – all at once? How the heck did we end up electing this guy?

To be sure, President-Elect Obama benefited from shifts in the social fabric – immigration, urbanization, and the rise of Gen Y. Just as crucially, though, he ran a political campaign that took a page from the business world – specifically, from the history of cell phone adoption.

As any marketer will tell you, it’s hard to get people to buy a new product. It’s harder still if that new product is something as radically different as a cell phone. When they first came out, cell phones were certainly not the mass-market phenomenon they are today. Their path to ubiquity is a classic case of adoption theory in action.

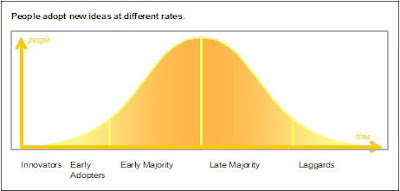

Source: Bryce Ryan & Neal Gross (1943)

The first people to use cell phones – the Innovators – were technology enthusiasts, people who love to try new ideas for the sake of their novelty. Between 1956 and 1983, 600 of these innovators signed up for the first mobile phone, Ericcson’s 90-lb Mobile Telephone System-A (its successor, a svelte 20 lbs, was released in 1965). Back the, the idea of a walking-around phone didn’t make sense to most folks.

The industry soon wised up, and started crafting a strategy aimed at Early Adopters, visionaries who selectively adopt new ideas in order to affect great change. Wall Street power brokers were the perfect Early Adopter group: they were affluent enough to afford pricey mobile phones, and they had an urgent need to communicate stock market information as quickly as possible. These Early Adopters showed the rest of us the benefit of a mobile phone.

By the late nineties, the mainstream started to warm up to the idea of purchasing a cell phone. In 1998, Nokia released the groundbreaking 5110, a mobile phone with colorful changeable faceplates. This product made the phone seem less like a complex device, and more like a fashion accessory. It showed ordinary people how something a mobile phone might, in fact, be a practical addition to everyday life. The 5110 was instrumental in getting the Early Majority on board with mobile phones. Not too long afterward, mobile phone prices dropped to near-commodity levels, spurring adoption by the Late Majority – a segment motivated more by peer pressure and necessity than by a vision for the future. Today, even most Laggards have cell phones (albeit decidedly low-tech ones).

Obama’s genius was in recognizing (perhaps implicitly) that “marketing” his own candidacy wasn’t altogether that different than marketing a cell phone. Like mobile phone manufacturers, Obama had to sequentially target each segment of the adoption curve in order to win over voters.

He started with the Innovators by explaining his “technology”: who he was and what he stood for. Much of this went on behind the scenes during his tenure in the Senate as he won over wonks, insiders, and political junkies. But Innovators alone can’t deliver an electorate. The next group, the Early Adopters, is far more influential in determining how an idea, a technology, or even a presidential candidate is later received in the marketplace.

As my colleagues Alonzo Canada, Pete Mortensen, and Dev Patnaik pointed out in a recent article in the Design Management Review, appealing to Early Adopter visionaries requires a narrow focus on iconic aspects of a new idea – just those parts that will set a vision for how things can be different. This is where Obama made his greatest mark. He set a vision for change, embodied by the refrain “Yes We Can!” He delivered speeches in Chicago and Iowa that invoked Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s ideals and sent chills down people’s spines. He helped people envision unification, individual promise, and collective achievement at a time when people felt divided, stymied, and undermined. That single phrase, and his powerful vision, captured the hearts and minds of the Early Adopters.

Just as Geoffrey Moore predicted in Crossing the Chasm, Obama’s next great challenge – one that almost sank his presidential ambitions – was making the leap from Early Adopters to the Early Majority. His visionary rhetoric was inspiring, but in order for the Early Majority to buy into it, they needed a more practical message. Opponents from both parties derided his campaign as high on rhetoric but low on specifics. Obama eventually shifted into a more pragmatic message to appeal to this practical segment. He toned down the vision and inspiration in his message, and turned up the specifics. He showed how his ideas would translate into specific actions that would affect the wallets, homes, jobs, and education of everyday American voters.

Of course, Obama couldn’t have been elected without also appealing to the Late Majority, folks who joined with him over the last several months. The recent economic crisis may even have forced him into a strategy designed to appeal to these harder-to-reach folks. Like cell phone manufacturers who increased their markets by decreasing the cost of the mobile device, Obama played his economic hand effectively. In the last few weeks, he showed how a vote for him was a vote for economic survival. With jobs disappearing, homes being foreclosed, and stocks in a slump, Obama demonstrated to the Late Majority that he was the right person to address their immediate, pressing economic concerns.

Last night, we found out that Obama’s adoption strategy worked. His campaign’s relentless drive to appeal to each segment of the adoption curve allowed him to introduce a set of new ideas, new approaches, and new thinking to an electorate that was badly in need of change. As remarkable as Barack Obama may be, he’s certainly not the only political candidate who can benefit from such an approach. In fact, other campaigns may equally benefit by harnessing cutting-edge thinking from the product development and marketing world.

As Obama proved, the road to success requires a simple adaptation of the strategies Canada, Mortensen, and Patnaik lay out in their article.

1. Convince the Wonks.

While the Wonks can’t deliver an electorate, they are the gatekeepers. If they don’t buy into your legitimacy, nobody else will, either.

2. Inspire the Change Agents.

Give the Change Agents – Early Adopters – a vision of what they’re working toward. Show them how you’re going to change your community, your region, or our world. Inspire them toward a better future.

3. Tackle the Pragmatists.

This is the part that bores the Change Agents, but is crucial to developing a critical mass of voters. Show how your vision translates to practical action. Speak in concrete, tactical terms. Cut the rhetoric, stick to specifics, and show that you know how to block and tackle.

4. Show the Skeptics What’s in It for Them.

The Skeptics are motivated by peer pressure and economic necessity. You can try to peer pressure them into voting for you, as Obama did, by creating a sense of community or belonging around your movement. This is harder to do if you don’t have his charisma. Alternatively, you can appeal to people’s bottom-line motivations, and show them that the biggest risk they face is in not voting for you.

5. Let the Skeptics Convince the Laggards.

Trying to convince the Laggards to vote for you is a fool’s errand. Like other groups in the adoption curve, they’re most likely to be convinced to adopt a new idea if the group before them is doing the convincing – in this case, the Skeptics. This also helps increase your return on campaign dollars, as this strategy relies on the (free) manpower of people who are already in your camp.

Candidate Obama ran a smart campaign – one that demonstrated a clear understanding of human issues as much as political issues. Let’s hope that President Obama’s administration will continue that tradition.